Cultural Organizing in Practice: What Does

it Look Like?

Cultural organizing is a strategy that aims to revitalize and sustain immigrants’ artistic expression and cultural practices. Following the values and guiding principles of popular education and participatory action research, we see cultural organizing as a concrete step toward building a community that is cohesive and capable of responding to social challenges.

Working in the context of culturally diverse communities like the Central Valley, cultural organizing also implies an intercultural learning process that encompasses understanding, respect for differences, and negotiating to engage in collaborative community-building practices. It also involves a cross-pollination of ideas and traditions among different ethnic groups living in the Central Valley.

Cultural Organizing Principles

• Cultural organizing broadens the conversations about the power of arts and culture for transformative social change

• We build political power by engaging with the influential tenets of cultural heritage, including local cultural knowledge and by validating the importance of tradition, language and indigenous expression

• We place specific focus on placemaking by engaging all aspects of place: local artists, local communities, local voices, local initiatives

• We believe that acts of creativity, self-expression and identity formation are central to activating change

• We are developing deeper understandings of the role

of artists, interdisciplinary conversations, and contexts

of place to build stronger, more active communities

Ideas for Practicing Cultural Organizing

• Provide spaces for expressing and sharing cultural

and artistic traditions

• Engage diverse cultures in the production of innovative cultural and artistic expressions to build vibrant and active communities

• Provide spaces for reflection and dialogues that address issues of cultural discrimination, colonization, internal colonization and internal oppression

• Get immersed in the community and develop inventories

of cultural assets

• Provide opportunities for regaining cultural knowledge

“Cultural organizing is a process by which immigrants, particularly indigenous communities, are provided with the opportunity to continue practicing their traditional cultural and artistic customs. Such practices help immigrants develop their sense of belonging by allowing them to share their cultural and artistic customs with other community members. Most importantly, cultural organizing promotes and supports the cultural preservation and identity of immigrants.”

Pat Lor

Principles

• Cultural organizing uses the arts and culture to bring about social change

Tips

• Cultural organizing is not just about organizing an event

• Cultural organizing has to be collective

• An event is the culmination of a learning and cultural exchange process

• Events have a social justice intention; they are not just about entertainment

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Cultural Organizing section tools

An Example of Cultural Organizing

This tool provides an example of what cultural organizing looks like in practice.

A Pan-Valley Institute Success Story

One of the intents of our cultural organizing work is to provide spaces, resources and opportunities for immigrants to reinstate their culture and creative expression. In 2006, we organized the Tamejavi Festival in Madera, Calif. with the goal of highlighting the presence and diversity of the Mexican indigenous that now call that city home. One of the roles of the members of the planning committee was to identify artistic and or artisanal skills within their own communities. Juan Santiago, a member of the planning committee, comes from a family where his mother and other women are palm weavers. Juan organized an intergenerational palm weaving workshop where the older women could teach the next generation the skill of palm weaving.

At this workshop, participants realized they needed to preserve the palm weaving knowledge that has distinguished the town of San Juan Coatecas Altas in Oaxaca, but they ran into a problem because the kind of palms they needed can only be found in Oaxaca. The Pan-Valley Institute provided resources to bring palms from Oaxaca, and the women were able to display their art of weaving palms at the Tamejavi Festivals of 2006, 2007 and 2009, and have since continued to weave palms.

Getting Started

Observe and learn what artisans exist within a community. These artists may be hard to identify since, as we have learned, many are no longer practicing their art. Once you identify the artists, provide them with the space to come together to recreate their art. This activity is important because they can reclaim their culture while they preserve cultural and artistic knowledge. They can share their knowledge with future generations.

“On a personal level I didn’t learn how to weave as I was supposed to; however, I was able to observe the weaving process and we eventually did other workshops. I saw that an important accomplishment was that we gained trust so that they could continue participating. I think the women felt a sense of belonging because they had the space to do their own art. They felt safe to share their knowledge because they felt they had something to contribute and were willing to do other workshops, including participating at the Tamejavi festival.”

Juan Santiago

Principles

• Increasing access to public space for cultural expression is key

• Popular participation in cultural production is integral to community life and civic engagement around the world

• There are no set formulas: by encouraging diverse participants to design cultural and art series, festivals and sharing opportunities, something new is created each time, and learning occurs along the way

Tips

• Some people, indigenous groups in particular, might not be to open to sharing their creative expression, art and artisanal knowledge; be patient, respectful, persistent, and keep opening the spaces

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Tamejavi Festival section

Tamejavi Heritage Gallery

This tool provides an example of what cultural organizing looks like in practice.

The Pan-Valley Institute has had success with our Tamejavi Heritage Gallery at past events. This tool, which provides an example of cultural organizing, provides advice for making your own heritage gallery.

Creating a Heritage Gallery

You can create a heritage gallery at meetings, retreats and residential gatherings. Invite attendees to these events to bring an object that represents their culture, art or any other form of creative expression. These spaces provide opportunities to communities whose creative and artistic expression have been ignored. When the objects that represent their culture are displayed in an aesthetically pleasing way, it helps the object’s owner feel validated and can give them a new appreciation for their culture.

How to Get Participants Involved

1. When planning a heritage gallery, send a letter to participants describing the gallery’s intention and asking them to bring an object that represents their community’s cultural and artistic traditions.

2. Let participants know that they should come prepared to make a presentation about the object they are bringing; i.e. what it is, if it has a utilitarian use, how it was made, its personal significance, etc.

3. In the letter, ask participants to send a photo of what they will be bringing so the coordinators of the gallery can start getting ideas of how to curate the exhibit.

4. Include a disclaimer in the letter that the coordinators are not responsible for the care of delicate items.

5. Make sure participants send the correct name and spelling of each item and include the English translation when necessary; this information will be used to label the objects.

6. Be very intentional about the aesthetics of the displayed objects, and exhibit clothing on mannequins whenever possible.

7. When the gallery opens, participants will be asked to tour the exhibit, examine each object and take their own notes and ask questions. Allow at least 30 to 40 minutes, depending on how many objects are being exhibited and the size of the group. Participants should consider the following questions:

• What did you see?

• Did you consider what you saw in the gallery to be art?

Why or why not?

• Think of a question you would like to ask about an object(s).

8. On an index card, each participant will write down the name of the object(s) that grabbed their attention, with one or two questions pertaining to the object, and drop the index card in a box.

9. Once participants are done visiting the gallery and have put their index cards in the box, the facilitator will begin to pull out questions and ask them to the indicated person. Allow 30 to 40 minutes, depending on the questions.

10. Participants will answer the question(s) pertaining to their object and brief discussions will take place.

Materials Needed: pens, index cards, box for cards

Principles

• Cultural exchange is about doing and learning; it’s not passive spectatorship

• Creating a safe learning space takes patience and is important when convening diverse groups

Tips

• Before the gallery is set up, visit the venue or space where the gallery will take place

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Tamejavi Festival tools

• Cultural Organizing tools

The Challenges of Cultural Organizing

in Poor Communities

Practicing cultural organizing can present many challenges, especially when working in poor communities. To help illustrate these challenges, this tool shares a reflection from Genoveva Vivar, one of the participants of the second cohort of the Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program (TCOFP).

When it comes to organizing newly established communities, such as the Mixteco indigenous community members of Tonyville, many obstacles occur along the way. When I was planning and organizing the “Ashamed No More” event, choosing the date, which one would think would be one of the easiest aspects of planning, became one of my biggest challenges. I had to work around the migration schedules of community members who are seasonal agricultural workers in places like Stockton, Oregon, and Washington. They typically leave around mid-May, and many don’t return to California until mid-August or September.

Even those that work agricultural jobs in the area may have limited availability. During the late summer grape season, the work day begins at 4 a.m. and may last until 7 or 8 p.m., making participation in anything outside of work very difficult.

When working with a community of seasonal farm workers, it may be best to plan events for the months of February through April.

A general lack of interest presents another challenge. People who aren’t normally involved in the community will be less likely to attend a community organizing event, but special events may attract those who are looking to get involved and didn’t know how. Despite the interest in my event from many of the men and women in my community to make the event a success, others failed to show any support or excitement.

“Cultural life in my community means being able to express yourself without the fear of being judged by others, the ability to speak your native language without others looking at you funny, and a capacity for artistic expression through music, cooking and sewing.”

Genoveva Vivar, TCOFP alumna

Principles

• Popular education places priority on the poor, oppressed and marginalized. It is aimed at accompanying these groups through the process of reaching a deeper understanding of their power to change their conditions of oppression

Tips

• Understanding and flexibility is very important when doing this work

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• The Glossary

• How to Make it Work I

Popular Education Poster

Who is a Cultural Organizer?

This tool list the abilities of a cultural organizer and provide ideas for identifying, recruiting and engaging groups of people in cultural organizing.

What Makes a Good Cultural Organizer?

A cultural organizer is someone who:

• Is committed to community work and collaborative processes

• Listens to the concerns and dreams of the community

• Understands the daily issues in the community and also

has a larger vision

• Makes links and connections between people, places and organizations

• Makes sure that the issues of the community are addressed

• Brings people together

• Knows how to build relationships in the community

• Understands the cultural patterns and understandings

of their community

• Comes from a diverse cultural background, believes in

collective learning and social change, and is committed

to making a more just and democratic society

• Has understanding of the economic, political and social

impacts that have shaped the immigrant and refugee communities

• Shares cultural organizing values and principles

Profile of a Cultural Organizer

Brenda Ordaz was born in Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico. The daughter of Zapoteco farmworkers, she was constantly on the move as a child until settling in Madera, Calif. at the age of 11. Besides attending college and working as an organizer for the Coalition for Human Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles, Brenda is also a committed cultural promoter. She spearheaded a youth dance ensemble to perform at the Fiesta del Pueblo, a yearly event in celebration of San Juan, the saint of her hometown. The Fiesta del Pueblo is not only a religious ceremony, but also the time of the year in which Zapotecos living in Madera have a space to play music, dance and display their art, culture and food. Brenda believes that this event gives a sense of belonging for youth and children of immigrants. She also wrote and performed in “The Fandango Zapoteco,” a play representing a traditional wedding.

By attending and organizing cultural events, Brenda has discovered the great needs and the organizing potential of the Zapoteco community.

During her time in the Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program (TCOFP), Brenda learned about cultural organizing practices by forming a learning group. She identified six people from her community and invited them to be part of her group. After the initial meeting in which she shared with them about her role as a TCOFP fellow and what their role in her learning group would be, she involved them in her community assessment and cultural inventory. The group later used what they learned to present a play telling the story of migration in her community. As a cultural organizer, Brenda was in charge of all the group’s meetings and activities while supporting their involvement and being receptive to their needs. At the end of her fellowship, she facilitated follow-up meetings in which group members shared what they learned about creating a space for their community to tell a story in their own voices.

“I want to plant a seed that will help my fellow immigrants develop a feeling of belonging, creating a strong sense of identity and personal strength to help them act on the issues that affect their lives.”

Brenda Ordaz

Principles

• Creating a space for the expression and reproduction of indigenous artistic and cultural knowledge is a decolonization step

• Cultural organizing is a collective process that works with groups, not just individuals

• Popular participation in cultural production is integral to community life and civic engagement around the world

Tips

• Be connected to the community

• Build community trust

• Have time, commitment and passion to engage in activities and follow through on the work agreed upon

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Learning Groups tools

• TCOFP tools

Cultural Organizer Vignettes

This tool shares profiles of cultural organizers that participated in the Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program (TCOFP).

Pov M. Xyooj was born in Long Beach, Calif. His parents are Hmong refugees who were sponsored to come to the United States from a Thai refugee camp through his mother’s father. He is the first in his family to be born in the U.S., and became the first to graduate from a four-year university when he earned a B.S. in physics and a minor in Asian American studies from UCLA. While in college, he was involved in several Asian student organizations, including Vietnamese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino and Hmong associations. Pov moved back to Fresno, where his parents live, after college and immediately started building connections with local Asian student organizations and community leaders. Through this work, Pov is not only reconnecting with his cultural roots and immersing himself in the Hmong community, he is taking action to redefine his identity by composing and performing bilingual hip-hop music and reclaiming his original Hmong family name.

Silvia Rojas is a native of Santiago Tiño Mixtepec, Oaxaca, Mexico who came to the United States in 1992 at the age of 17. Silvia speaks her native Mixteco, Spanish, and understands some English. Like many other women from low-income immigrant families, Silvia assumed major social responsibilities from a very young age, including running her hometown medical clinic at the age of 13. Since moving to the U.S., Silvia has worked in agriculture, harvesting onions, garlic and strawberries. Now married and the mother of two boys and three girls, Sylvia no longer works in the fields and dedicates much of her time to community work. Besides her commitment to motherhood and community organizing, Silvia loves dancing and has participated in the traditional dance group Se’e Savi in Madera, Calif. As her commitment to the dance group’s community work grew, she became a member of Se’e Savi’s organizing committee. In 2006, Silvia was invited to participate in a project called Naaxini (leader) where she learned to be a health leader to help the indigenous immigrant community.

“Ultimately, cultural organizing utilizes culture and art as a venue and resource for strengthening immigrant leadership and building a sense of place and belonging that inspires and promotes active participation in public life.”

Juan Santiago

Principles

• We give people the tools they need to make changes in their communities

Tips

• To be a cultural organizer, you must be willing to invest time and have a special interest in the cultural vitality of the community

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• TCOFP tools

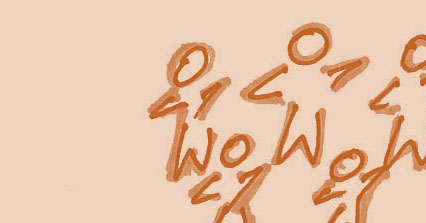

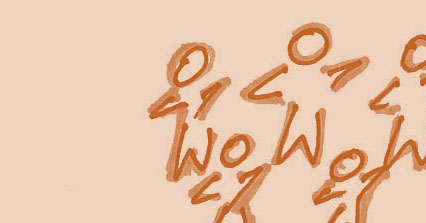

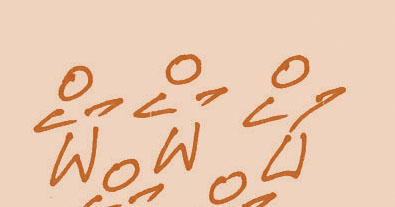

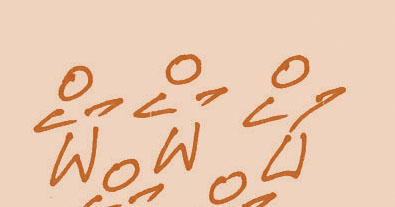

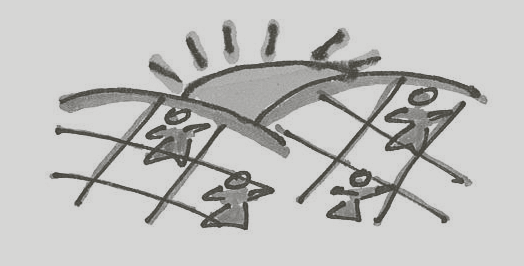

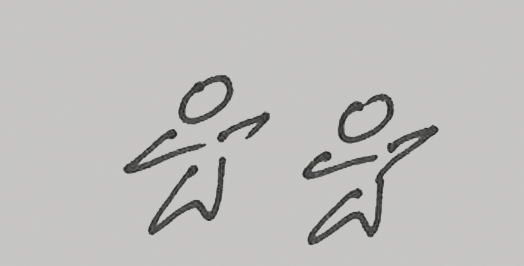

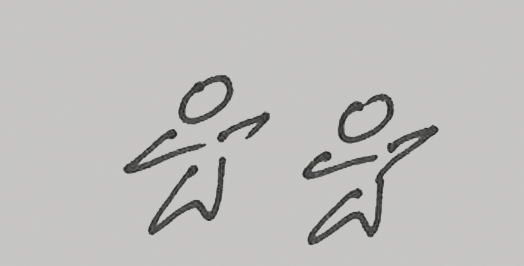

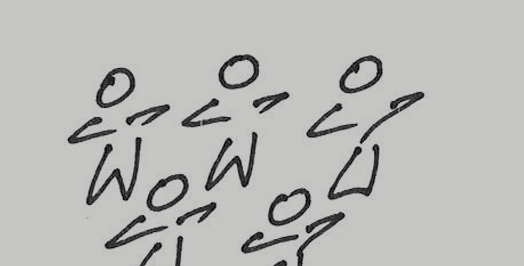

Graphic Facilitating

Graphic facilitating has been a tool since the early years of the Pan-Valley Institute’s inception.

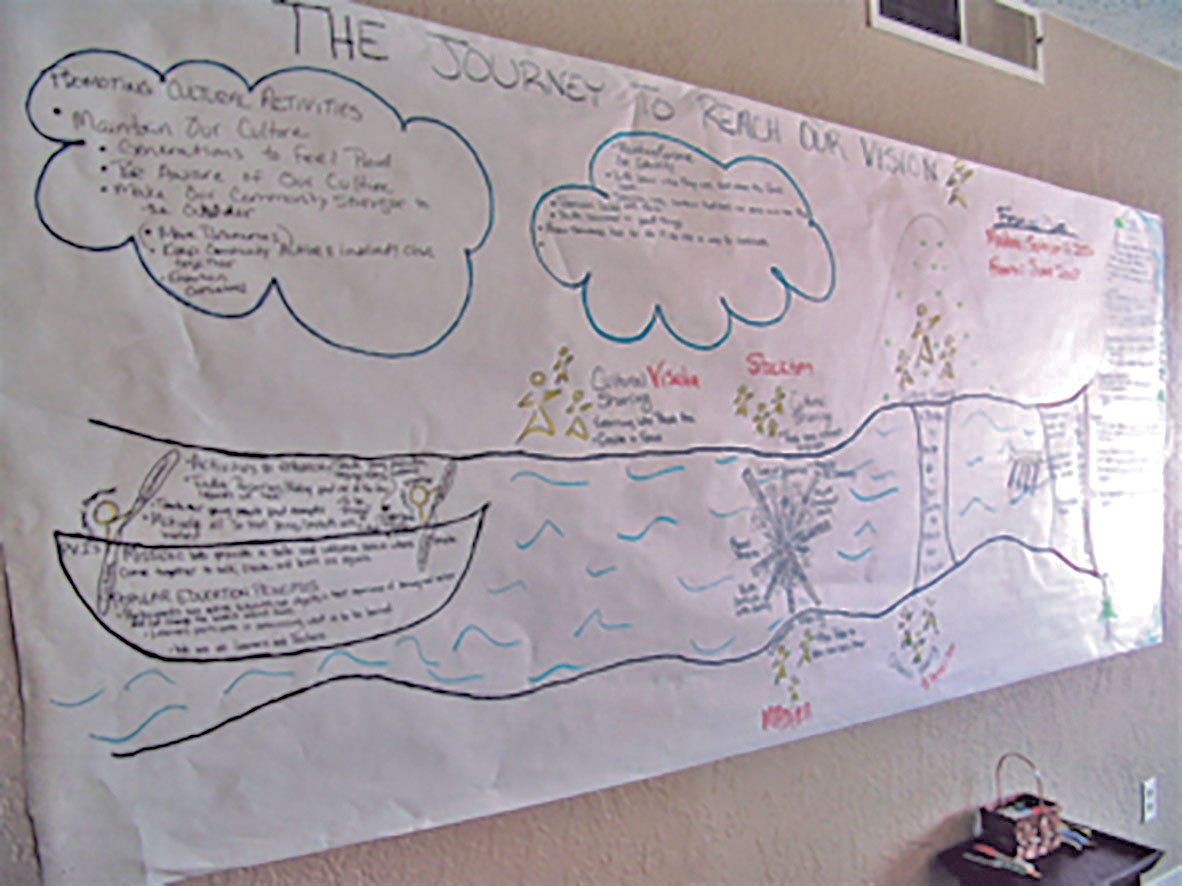

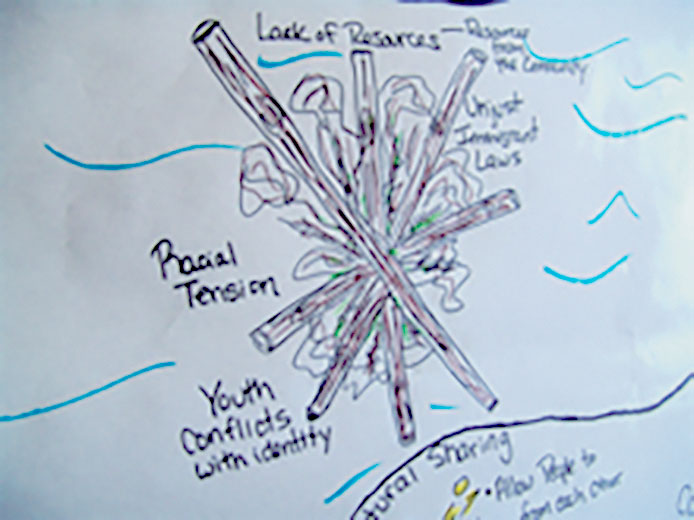

In this tool, we share an example of a poster developed to describe the steps of a cultural organizing process and the journey cultural organizers take to reach a vision. In the clouds, we describe the intention of cultural activities, the boat indicates the cultural organizers embarking on their journey and the different steps they take to reach their vision, along with the obstacles they face. It includes the people they meet and bring together in the process and the different events they organize before the culmination of the journey.

Principles

• There are no set formulas; by encouraging diverse participants to design cultural and art series, festival and other cultural sharing events, something new is created each time and learning is created each time

Tips

• Be creative, as creativity is the key to this process

• Develop your own approaches

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• How to Facilitate the Popular Education Process Tool

• The Practitioner’s Role in Popular Education Tool

What is a Learning Group?

This tool will provide information about what constitutes a learning group and learning group principles.

In the summer of 2001, a committee of the Pan-Valley Institute (PVI) staff, Central Valley Partnership for Citizenship (CVP), and members of the Civic Action Network (CAN) conceived the idea to design a festival that used cultural expression and the arts to bring immigrant communities into the public square, create a forum for their voices, and encourage civic engagement. The first Tamejavi Festival demonstrated that intercultural learning can play an important role in creating relationships built on trust, collective knowledge, and public voice in order to build stronger communities and increase civic engagement.

To continue this process, the idea of forming learning groups came about with the intention of engaging immigrant and non-immigrant communities in intercultural learning. For the second Tamejavi Festival that took place in 2004, we formed different groups based on different media or artistic skills. We had a documentation learning group, theater learning group, youth learning group and a women’s learning group, with each group in charge of their component of the festival. This became an effective approach because it was a collective process that decentralized the organizing of event, and it helped group members contribute their existing knowledge while continuing to increase their knowledge and skills.

For our Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program (TCOFP), this idea of forming learning groups was an effective approach because it extended the fellows’ opportunities to others in their communities. The exercise helped fellows demonstrate their convening capacity and ability to engage people in a collective learning process. Fellows who did not form a learning group learned that they had to do most of the work themselves and did not create a collective process.

How Do Learning Groups Work?

One person from each group is appointed as cultural organizer, or head of the group. This person is responsible for engaging the group in activities and keeping them organized and updated on current events. Each learning group will meet on a consistent basis and engage in self-initiated activities, meaning that each group will hold these activities on their own. For example, the Dance Learning Group may want to plan an evening where the Folkloric, Hmong and Cambodian dancers come together to learn one another’s dance routines, and most importantly, discuss the cultural significance of the dances.

What is the Goal of Each Learning Group?

Throughout the process of engaging in self-initiated activities and meetings, each learning group will create a Collaborative Learning Project that will reflect a merging of the different cultures within that group. For example, the Dance Learning Group may decide to create a dance routine that incorporates styles of Folkloric, Hmong and Cambodian dance while also reflecting transformations of the style through the immigrant experience.

Principles

• Creating a safe learning space takes patience and is important when convening diverse groups

Tips

• When recruiting members for learning groups, if the first thing you hear from a person is that they are too busy, it is an indication that he or she may not be an effective member

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work Tool

• Who is a Cultural Organizer? Tool

• TCOFP Tool

• Glossary

Learning Group Principles and the Roles

and Characteristics of Members

This tool provides learning group principles and information on the roles and characteristics of effective learning group members.

Learning Group Principles

• Enrich Community Cultural Life: Learning groups promote understanding and appreciation of cultural diversity.

• Build and Promote Civic Engagement: By dignifying cultural background and opening spaces for cultural expression, learning groups allow participants to develop a sense of community belonging.

• Build Local Capacity: Learning groups promote alliances with community stakeholders and professional resources.

• Encourage Diverse Collaboration: Learning groups nurture a diverse environment that allows groups and people of different ethnic backgrounds to come together and collaborate on a unified project.

• Thematically Focused: Learning groups focus on centralized themes, allowing for commonality and cohesion between group members.

• Promote Art and Culture: Learning groups foster appreciation of the arts while also cultivating cultural awareness.

• Uphold Values of Learning: Learning groups maintain that the process of learning is continual; we are always teaching one another so that we are always learning from one another in return

Learning Group Members Roles and Characteristics

The learning group is crucial to the development and decision-making process of the Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program (TCOFP). We have learned that effective learning group members have the following roles and characteristics:

• Share the importance of art and culture as venues for organizing and community building

• Believe in collective learning and social change, and are committed to making their community a more just and democratic place

• Do outreach work in their community by engaging community members in a learning process, assisting their community in developing forms of arts and cultural expression for the public presentation, and by building audiences for the presentation

• Attend monthly mandatory meetings

• Engage in cultural organizing and activities and follow through on work agreed upon

• Recruit volunteers for public presentations and/or recruit sponsors and donations

Principles

• Start from people’s own experiences

• People work collectively (in groups), share experiences, and encourage participation

Tips

• Have a recruitment criteria

• Members should be interested and committed

• Never force anyone to be part of a learning group

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work Tool

• Glossary

• TCOFP Tools

Learning Group Formation

This tool provides steps for the formation of a learning group.

Who Should You Invite?

Invite a solid team of allies that will engage with you in planning, assessing and reflecting about all aspects of your cultural organizing work. They should also be willing to involve other community people in cultural organizing.

Recruitment

• Recruit people who have a sense of community and are engaged and interested in organizing for social change.Be gender, age and educational level inclusive.

• The learning group should be as representative of the community as possible.

• Learning group members should have connections to the key community people you will need to inform and/or ask for further information, advice and help from as the program moves forward.

• Choose members who are comfortable working as a team. Avoid those who feel so “expert” or educated that they will likely tell the others what to think or do.

• When recruiting a team member, explain your role as a cultural organizer and popular educator who has taken on the responsibility to facilitate the effort and make sure things are moving forward.

• When recruiting a team member, explain why you are approaching them to engage with you in a cultural organizing process.

How Many Members Should Be in a Learning Group?

You should include five or hopefully more community members who want to volunteer their time because they share your vision, are interested in building robust communities, and are excited about doing cultural organizing work.

The number of people in a group has great influence over the group dynamics. For interactive processes and nurturing collective leadership, smaller groups are recommended. When the group is too big, there are fewer opportunities for each person to share and participants tend to lose focus.

Success Story

When participating in the Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program (TCOFP), Cher Teng Yang (also known as Bee Yang) formed a multigenerational and gender diverse group of Hmong youth and adults who were involved in art and cultural activities within the Hmong community. Cher Teng Yang’s group was very effective because most of its members shared a common interest and had a deep understanding of the importance of art and cultural expression. It also helped that Cher Teng Yang is a cultural holder and well-respected member of his community. Throughout the fellowship program, they met regularly and worked well together, resulting in the presentation of a beautiful and well-organized event.

Principles

• Start from people’s own experiences

• People work collectively (in groups), share experiences, and encourage participation

Tips

• Have a recruitment criteria

• Members should be interested and committed

• Never force anyone to be part of a learning group

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work Tool

• Glossary

• TCOFP Tools

Building A Shared Agenda:

Relationship Building

The process of setting a shared agenda is essential for building meaningful relationships that lead a group to engage in collective action. This tool will explain what that process can look like.

Sharing an agenda is one of the key steps in groups formation as it helps the group have a clear understanding of the following: who are the members of the group; the skills and knowledge each member brings to the group; the ground rules that will guide the group; goals and motivations for engaging in an action; and projects and problems that most concern the group.

A shared agenda has five components:

1. Relationship building, allowing group members to get to know each other

2. Establishing group ground rules and guidelines

3. Identifying group assets and the skills each member brings to group

4. Establishing group goals and objectives; what would the group like to accomplish?

5. Identifying specific issues of concern to the entire group

Relationship Building

After you have recruited members of your learning group, the first time you come together is an excellent opportunity to do an exercise that allows all members to introduce themselves. This can be done using different activities like the Tree of Life, a story circle or any other activity you can think of. Here is an example.

Starting with Ourselves Activity

Objective: to provide the group the opportunity to learn about one another. Time: 1 hour

1. Instructions, 3 minutes

Draw a picture of yourself that maps out your own perspectives and experiences using imagery that best represents your life. Provide only information you want to share at this time with a group of people you are meeting for the first time.

2. Answering questions, 40 minutes

Center of the body – what is at the core of the lifework you aim to participate in?

Eyes – what are the injustices or experiences you find yourself observing or living?

Feet – what are the main events and experiences that shaped your life so far?

Backbone – what gives you strength?

Arms – share a story about the main people who have affected your life, then share a story about people whose lives you’ve touched.

Head – what are the main ideas or realizations that guide your life and work?

Environment – have you ever taken a stand on an important issue?

3. Sharing, 10 minutes each

Principles

• The learning has to be relevant. We do not have curriculum because each group has to decide what they want to learn.

• People are more motivated/interested in organizing around issues that are relevant to them.

Tips

• It takes time for a group to get to get to know each other; this doesn’t happen with one activity

• Allow informal time for people to get to know each other

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work Tool

• Glossary

• Convening Learning Groups tools

• Popular Education Section How to Make it Work I

Building a Shared Agenda: Group Ground Rules, Guidelines & Assets

Group Ground Rules & Guidelines

The second step for building a shared agenda is to establish ground rules and guidelines under which the group will operate.

Think about and agree upon guidelines needed in order for the group to feel comfortable working and learning together.

When working with the group, try to remember the best and worst learning experiences you have had working with a group. These could be from school, community organizing, staff training or some other formal or informal situation when you were hoping to learn something or collaborate on an action or project.

Based on these experiences, what group guidelines would you suggest in helping the group create the kind of learning setting in which everyone feels comfortable and respected?

Use those suggestions to draw up a set of guidelines that everyone can agree to. For example:

• A safe, comfortable, democratic atmosphere in which everyone can learn and contribute freely Open mind, open heart

• Everyone is expected to respect and value each other’s point of view

• Establish open communication with one another

• Respect each other’s culture without judgement

• Have an open mind and willingness to learn from everyone

• Everyone should communicate and listen to one another

• Open mind, open heart

These are just examples; your group has to decide on their own guidelines.

Group Assets

This section of the shared agenda allows you to explore the skills, knowledge and expertise that each participant brings to the group. Spend time thinking about the knowledge, expertise and skills you have, whether they are cultural, artistic, etc. Don’t list only academic skills, but also knowledge you have gained and expertise you have acquired from your parents, elders and others. Consider the following:

• The main knowledge I hold is…

• I have expertise in…

• I am talented and skillful at…

Principles

• Necessary to value knowledge, experience of all people. Everybody has knowledge, everybody brings something to the table. Start with what people already have.

Tips

• Allow time and space for all to contribute to the group guidelines

• Keep the guidelines visible at all meetings

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work Tool

• Glossary

• Convening Learning Groups Section

Building a Shared Agenda: Group Intentions & Talking Points

This tool provides ideas for allowing the learning group to establish goals for being together, from each individual to the entire group.

Groups Intentions

During this session, you will:

• Explore what you hope to achieve individually as part of this group

• Explore what you hope your group will achieve together

• Agree on the group’s goals

• Consider how the group’s learning activities and other achievements can be evaluated

Spend time thinking about what you’d like to get out of the work you will be doing with the group. If possible, write it down or talk it through with someone else in the group first before getting into a group discussion about it. Try to think in terms of your overall intention and then list anything else you are personally hoping to gain or achieve.

Consider the following:

• My main intention in coming here is to…

• I would also like to…

Talking points

• Do we have similar reasons for being here?

• Do any members feel that their needs or expectations

can’t be met?

• If we had to agree on our overall aim or goal, what

would it be?

• Do we have a shared view of how we intend to get there?

• Can we list any other group objectives or goals?

• How do we intend to achieve them?

• How will we know where we’ve achieved these aims

and objectives?

• How will we evaluate what we’ve learned or achieved together?

• How can we make sure that we learn from any mistakes

as we go along?

Principles

• People are more interested/motivated in organizing around issues that are relevant to them

Tips

• This section is very important, and it’s fine if you need more than one meeting; don’t rush the process

• When the group is clear from the beginning as to why they came together and what they hope to accomplish, the group will be successful

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work Tool

• Glossary

• Convening Learning Groups Section

• Popular Education Section How to Make it Work I

What is Cultural Sharing?

This tool provides information about what cultural sharing events looks like, how they are structured, and the different forms they can take.

Definition of Cultural Sharing

Cultural sharings provide a space for people to come together across cultural lines to learn from one another while re-asserting their cultural traditions, meanings and voices to themselves and others. Doing so helps establish the sense of belonging and connection necessary for meaningful civic participation.

Why are Cultural Sharings Important?

Cultural sharings are a key strategy for building more inclusive communities in ethnically diverse places such as California’s Central Valley because they provide opportunities for community relationship-building through intercultural learning and awareness. Cultural sharings encourage first-hand learning, visiting one another’s communities, and building a safe, respectful cultural learning environment where people from all backgrounds feel welcome.

How are Cultural Sharings Structured?

Cultural sharings are one-day events that can take the form of a cultural kitchen, a bus tour, thematic sharings and dialogues, or story circles through artistic mediums such as photo exhibits, videos, and/or performances. They can also take the form of community visits by attending a traditional celebration, cultural center, community garden or a community tour.

FORMS OF CULTURAL SHARINGS

Cultural Kitchen: The cultural kitchen provides an opportunity to learn and listen to stories of how diverse cuisines make their way to Valley homes and markets.

Dialogues/Pláticas: We intentionally use the word platica because that is the atmosphere we would like to create. It is a space in which we invite experts to give a brief exposition on the topic of the platica to prompt a conversation in which all or most attendees participate, either by asking questions or adding to the conversation.

Thematic Cultural Sharing: An example could be around the theme of traditional medicine, folk tales, oral traditions, poetry, music, dance, or any other central theme.

Visiting Events: These provide an opportunity for first-hand learning by visiting one another’s culture and art events.

Success Story

On a hot summer morning, participants of the Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program (TCOFP) and members of the coordinating group were invited to an intimate cultural kitchen hosted by Cher Teng Yang (also known as Bee Yang), a TCOFP fellow and his family. He invited the group to his home to learn how to prepare egg rolls and traditional papaya salad. All participants had the opportunity for the hands-on experience of making egg rolls, which Cher Teng Yang explained are from China, but were adapted by the Southeast Asian community make the recipe their own. He shared that when there is a big family event in the Hmong community, everyone has a role to play in preparing food for the entire family. Cooking together is seen as passing on culinary traditions, especially to the younger generations. Cher Teng Yang also gave participants a tour of his garden while sharing stories of his family life back in Laos. He further explained how his family finds ways to recreate important traditions as they learn new cultural practices.

Principles

• Provide a welcoming learning space

• Provide safe space where people can share life experiences

• Provide space for deeper cultural diversity insights and knowledge

• Offer space for socially excluded communities to share their cultural history and traditions in their own voices

Tips

• We recommend bringing a small group of participants to allow dialogue, interaction and opportunities for deeper learning

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Glossary

• Cultural Sharing Section

• Popular Education Section How to Make it Work I

Convening a Cultural Sharing

This tool provides the steps for convening a cultural sharing, as well as some protocols to consider.

Purpose: To create an intentional and meaningful space for cultural exchange and building cross-cultural relationships.

STEPS FOR CONVENING A CULTURAL SHARING

1. Convene a meeting with your learning, planning or coordinating group to decide if and why the time is right to facilitate a cultural sharing

2. The group should decide what they want the event to accomplish; identify the central focus of the cultural sharing, including the short and long-term impacts and changes you would like to see result from the event

3. Decide the kind of cultural sharing that will be most suitable for accomplishing the group’s goals

4. Contextualize your cultural sharing within the present social and political climate related to immigrants and refugees or other groups involved.

5. Create a theme/title for your cultural sharing; the title is the key message, not just a name

6. Conceptualize your cultural sharing as a strategy for building cross-cultural relationships and ties of solidarity for working together to address issues of interest to the immigrant communities in your area

7. Make a list of who you would like to include in the cultural sharing and the various organizer and volunteer roles

8. Develop an outreach plan

9. Be mindful of the artistic component, as this is a key element of cultural sharings

10. Identify the artist, cultural holders or story tellers for your cultural sharing

11. Generate a general planning document that includes a detailed logistical list and tentative program flow

CULTURAL SHARINGS PROTOCOLS

• Value the fact that a community is willing to share their culture, and be mindful and respectful

• Cultural sharings are not parties or events, but intimate gatherings among diverse cultures with the sole intent of learning from each other and building relationships

• Learn about the protocols of the community you are visiting and keep them in mind throughout your visit

• Entering into a community has to be facilitated by a member that has deep cultural knowledge and community trust

• When visiting another community, come with an open mind and heart; leave all prejudices and preconceptions aside, or come prepared to challenge those prejudices

• Have an attitude of mutual exchange, meaning that if you want people to learn about your community, you need to be open to learning about their community, including tasting their food

• There has to be a certain level of trust within the group

• Do not extend the invitation to others without first consulting the organizers of the gathering, and avoid bringing people who want to visit an “ethnic” community for their own benefit

• Ask if you can take photos before doing so as this is not a photo opportunity, but a learning opportunity

• Cultural ceremonies and faith practices require special guidelines and preparation before attending

Principles

• There are no set formulas: by encouraging diverse participants to design gatherings and festivals, something is created each time and learning occurs along the way

• Creating a safe space takes patience and is important when convening diverse groups

Tips

• Tips are included in the tool

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Glossary

• Cultural Sharing Section

• Tamejavi Festival Section

Cultural Kitchen: Who’s at the Table?

This tool provides information on what a cultural kitchen is and the steps to take when organizing one.

Background: The cultural kitchen concept initially began in the late 1990s and early 2000s with the Pan-Valley Institute’s women’s group, but wasn’t well defined until the second Tamejavi Festival in 2004. As a pre-festival event, cultural organizers would gather and share dishes that were significant in their communities as a way to build new relationships and trust among the group.

Purpose: The cultural kitchen provides space to explore cultural identity through traditional dishes from diverse communities and allows for dialogue around food to redefine what “gourmet” means. The cultural kitchen presents immigrant cuisines from the chefs and entrepreneurs emerging from immigrant communities and displays how the U.S. is gaining new flavors, adding to an already rich cultural diversity.

Definition: The cultural kitchen provides an opportunity to learn and listen to stories of how diverse cuisines make their way to homes and markets. This cultural space will activate participants’ senses while they enjoy the aromas and flavors of different herbs, spices and crops. It serves as an exercise to strengthen multiethnic relationships by learning about the common migration journeys of people who carry with them their cultural practices.

Creating Space for a Cultural Kitchen: Ask each participant (chef) to come prepared with a traditional dish they would like to share, specifying that it should have special meaning to them and/or their community. During the cultural kitchen, there will be stations assigned to each chef.

Aesthetics: Encourage each chef to design and curate their space by displaying ingredients they use for their meal, as well as traditional utensils they use for cooking and serving.

Sharing: The facilitator will begin the presentation by going from station to station. Some questions the chefs should be prepared to answer could include:

• Talk about the ingredients and nutritional value of your dish.

• Are the ingredients easy to find here; how do you get access to them?

• How did you learn to cook what you will be sharing?

• How long does it take to prepare? Is it prepared only for special occasions?

• Have you modified the dish since arriving to the U.S.?

• Share a story associated with your dish.

• Talk about the cultural meaning of your traditional kitchen utensils and tableware.

Success Story: In May 2006, cultural organizer Rosa Lopez, along with other community members, organized “Our Cultural Kitchen,” inviting diverse indigenous communities from Madera, Calif. The groups who participated were from the Zapoteco, Mixteco, Otomi and Purepecha communities. The cultural sharing engaged many people, especially youth.

During the cultural kitchen, participants created a space where they shared a dish significant to their cultural identity and community. Organizers hoped that through the cultural kitchen, non-indigenous people would have a better understanding of how they contribute to the Central Valley. They felt that by sharing their culinary expertise, it would share a message of cultural pride and honor the traditions they hope to pass on to future generations. As part of the cultural kitchen, there was a photo exhibit that illustrated the contributions of farmworkers.

Principles

• There are no set formulas: by encouraging diverse participants to design gatherings and festivals, something is created each time and learning occurs along the way

• Creating a safe space takes patience and is important when convening diverse groups

Tips

• Make sure you have an estimate of attendees prior to the cultural kitchen so the chefs know how much food to prepare

• Choose a location that can accommodate a cultural kitchen

• Ask the chefs to arrive two hours early to set up their stations

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Glossary

• Cultural Sharing Section

• Tamejavi Section

Central Valley Bus Tour

This tool illustrates an example of a cultural sharing learning activity that took place in the form of a bus tour through California’s Central Valley.

Background:

The Central Valley Bus Tour was created for the Civic Action Network (CAN), a small grantee program of the former Central Valley Partnership for Citizenship. CAN was formed by grassroots non-profit organizations from throughout the Central Valley, and organizers thought a bus tour would provide a unique opportunity for South Valley CAN members to visit organizations in the North Valley, and vice versa. The intent was to help them learn and understand more about one another’s communities by experiencing them firsthand.

Story:

CAN participants from the south and central areas of the Valley gathered at the Tower Theater in Fresno to embark on a trip to visit North Valley CAN members for a day of collective sharing and learning. To get things started, eight local poets and musicians, complete with journals and a sparse assortment of instruments, began tackling (through words) a wide array of social issues.

First Stop: Fresno Metro Ministries

Started in 1970, Fresno Metro Ministries focuses on relationship building within the community. They are a faith-based organization that works to create a more respectful, compassionate and inclusive community that promotes social and economic justice.

Bus Ride

As the bus traveled through the Valley via Highway 99, Professor Isao Fujimoto acted as tour guide and shared various facts about the Central Valley. He pointed to signs indicating where Japanese concentration camps were located during World War II, explaining that concentration camps were easily made; all that was needed was a racetrack or fairgrounds and some barbed wire to create a confined territory.

Second Stop: Portuguese Education Foundation of Central California,

TurlockIn Turlock, we met with Elmano Costa and Fatima Fontes, coordinators of VALER and the Portuguese Education Foundation of Central California. VALER helps the community by figuring out what services a person needs and helping them fill out the forms necessary to get those services.

Final Stop: COPAL:

The C.O.P.A.L. program started two years ago. It teaches young people about the importance of things passed on from indigenous communities.

Conclusion:

Professor Isao Fujimoto ended the evening by inviting the group to look at a map of the Central Valley and asked that they remember the purpose of the tour: “Don’t take anything for granted, look further, and ask questions.”

Principles

• There are no set formulas: by encouraging diverse participants to design gatherings and festivals, something is created each time and learning occurs along the way

• Creating a safe space takes patience and is important when convening diverse groups

Tips

• Know beforehand how many people will be participating to help plan for food and transportation logistics

• Choose destinations that can accommodate the whole group

• Ask all participants to arrive 30 minutes before scheduled departure

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Glossary

• Cultural Sharing Section

• Tamejavi Festival Section

INTRODUCTION

What is Tamejavi?

A word inspired by the creative antics of poet Juan Felipe Herrera, “Tamejavi” brings together syllables from the Hmong, Spanish and Mixteco words for marketplace: TAj laj Tshav Puam (Hmong), MErcado (Spanish) and nunJAVI (Mixteco). The combined syllables spell Tamejavi, representing a public place for the Central Valley’s diverse immigrant and refugee communities to gather, engage in cultural sharing and celebrate their work through building a sense of place and belonging.

WHAT DOES TAMEJAVI STRIVE TO ACHIEVE?

• Amplify the voices and increase pride of immigrant communities.

• Build new relationships and understanding across immigrant cultures and with other Valley residents who share a commitment to increasing civic participation and public recognition for diverse communities.

• Create a public space for creative expression that fosters civic engagement.

• Strengthen skills and build models for civic engagement through cultural sharing.

TAMEJAVI ORGANIZING PRINCIPLES

1. Popular participation in cultural production is integral to community life and civic engagement around the world.

2. Tamejavi activities grow organically from and are democratically organized by members of the Pan-Valley Institute, Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program fellows, learning groups, partners and interested Valley communities.

3. There are no set formulas: by encouraging diverse participants to design gatherings and festivals, something new is created each time and learning occurs along the way.

4. Creating a safe learning space takes patience and is important when convening diverse groups.

5. Multi-lingual and broad-based communication strategies are important to engaging diverse communities.

6. Attracting diverse audiences is as important as presenting multiple forms of expression.

7. Tamejavi both incorporates learning from experienced artists, presenters and cultural workers and believes that participating groups have the capacity to make decisions about the direction and presentation of their work.

8. Increasing access to public space for cultural expression is key.

9. Cultural exchange is about doing and learning; it is not passive spectatorship.

10. When combined, cultural exchange and community organizing increase the impact of local efforts to improve Valley communities and strengthen organizing networks.

Tamejavi is unlike other multi-cultural festivals and events

in several ways:

• Tamejavi is a daylong gathering to celebrate and experience the rich traditions of California’s Central Valley through visual and performing arts that is free to the public.

• Tamejavi is an important event for the cultural vitality of this region. It’s developed by a year-round learning community comprised of youth and elders, artists and organizers, chiefs and healers, educators and students.

• Tamejavi is designed to specifically foster meaningful civic engagement by immigrants with the established community. It provides a public space for immigrants to re-create the sense of community they experienced in their home countries and, in doing this, to build a sense of their own place.

• Tamejavi shares rich traditions in multiple cultural groups across cultures, experiences and languages. There is virtually no other place in America where you could find a traditional Mixtec singer followed on-stage by a Hmong spoken word artist.

“I want to plant a seed that will help my fellow immigrants develop a feeling of belonging, creating a strong sense of identity and personal strength to help them act on the issues that affect their lives.”

Brenda Ordaz

Principles

• Principles are included in tool

Tips

• Tamejavi is not just an event; it is a learning and cultural exchange process

• Tamejavi challenges and presents a new definition

of what art is

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Glossary

• Learning Groups Section

• Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program Section

• Popular Education Section How to Make it Work I

What is a Learning Group?

This tool will provide information about what constitutes a learning group and learning group principles.

In the summer of 2001, a committee of the Pan-Valley Institute (PVI) staff, Central Valley Partnership for Citizenship (CVP), and members of the Civic Action Network (CAN) conceived the idea to design a festival that used cultural expression and the arts to bring immigrant communities into the public square, create a forum for their voices, and encourage civic engagement. The first Tamejavi Festival demonstrated that intercultural learning can play an important role in creating relationships built on trust, collective knowledge, and public voice in order to build stronger communities and increase civic engagement.

To continue this process, the idea of forming learning groups came about with the intention of engaging immigrant and non-immigrant communities in intercultural learning. For the second Tamejavi Festival that took place in 2004, we formed different groups based on different media or artistic skills. We had a documentation learning group, theater learning group, youth learning group and a women’s learning group, with each group in charge of their component of the festival. This became an effective approach because it was a collective process that decentralized the organizing of event, and it helped group members contribute their existing knowledge while continuing to increase their knowledge and skills.

For our Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program (TCOFP), this idea of forming learning groups was an effective approach because it extended the fellows’ opportunities to others in their communities. The exercise helped fellows demonstrate their convening capacity and ability to engage people in a collective learning process. Fellows who did not form a learning group learned that they had to do most of the work themselves and did not create a collective process.

How Do Learning Groups Work?

One person from each group is appointed as cultural organizer, or head of the group. This person is responsible for engaging the group in activities and keeping them organized and updated on current events. Each learning group will meet on a consistent basis and engage in self-initiated activities, meaning that each group will hold these activities on their own. For example, the Dance Learning Group may want to plan an evening where the Folkloric, Hmong and Cambodian dancers come together to learn one another’s dance routines, and most importantly, discuss the cultural significance of the dances.

What is the Goal of Each Learning Group?

Throughout the process of engaging in self-initiated activities and meetings, each learning group will create a Collaborative Learning Project that will reflect a merging of the different cultures within that group. For example, the Dance Learning Group may decide to create a dance routine that incorporates styles of Folkloric, Hmong and Cambodian dance while also reflecting transformations of the style through the immigrant experience.

Principles

• Creating a safe learning space takes patience and is important when convening diverse groups

Tips

• When recruiting members for learning groups, if the first thing you hear from a person is that they are too busy, it is an indication that he or she may not be an effective member

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work Tool

• Who is a Cultural Organizer? Tool

• TCOFP Tool

• Glossary

INTRODUCTION

Tamejavi Coordinating Group/Planning Committee

This tool provides information on the role of a coordinating group/planning committee, and tips for recruiting committee members.

The Planning Committee’s Role

The Tamejavi Planning Committee is crucial to guaranteeing a collective process. This group also plays an important role in the planning, shaping and decision-making process of the event. The committee is formed of individuals representing one or more of the communities that constitute the base of Tamejavi. The principles of the committee and the roles of members are as follows:

• Members share Tamejavi values and principles

• Members believe in the importance of art and culture as tools for organizing and community development

• Members come from diverse cultural backgrounds, believe in collective learning and social change, and are committed to making the Central Valley a more just and democratic place

• Members make links and connections between people, places and organizations

• Members do outreach work in their community:

≈ by engaging community members in the Tamejavi learning process;

≈ by assisting their community in developing forms of arts

and cultural expression for the festival;

≈ and by building audiences for the festival.

• Members attend mandatory monthly meetings

• Members engage in Tamejavi activities and follow through on work agreed upon

• Members can recruit volunteers, register people in workshops/forums, and/or recruit sponsors and donations

• Members provide feedback on festival design

Recruitment Tips

• Recruit people who have a sense of community

• Reach out across gender, and people fron varied ages and educational levels

• Choose members who are comfortable working as a team

• When recruiting a team member, explain why you are approaching them to engage in a cultural organizing process as part of the planning committee

• Clearly explain the role of the planning committee

• Be up front about the time commitment

Success Story

Throughout the planning of various Tamejavi Festivals, there were those who were with us from the first festival in 2002 to the fifth festival in 2009. However, for each festival, there were new people who joined the committee. The group was always culturally diverse, multigenerational and each member had a different set of skills and played different roles. For example, the committee for the 2009 festival was formed by a member of the Iranian community who is a librarian and two members of the Native American community–one a musician and the other a muralist. One member that participated since the second festival played a key role in providing technical and curating support. Two of the members provided support with communication and documentation. There was a graphic designer and a person in charge of coordinating volunteers. Aside from the tasks they were assigned according to their skills, committee members were also influential in deciding on a theme, shaping the festival, outreach and promotion.

“I want to plant a seed that will help my fellow immigrants develop a feeling of belonging, creating a strong sense of identity and personal strength to help them act on the issues that affect their lives.”

Brenda Ordaz

Principles

• Principles are included in tool

Tips

• Tamejavi is not just an event; it is a learning and cultural exchange process

• Tamejavi challenges and presents a new definition

of what art is

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Glossary

• Learning Groups Section

• Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program Section

• Popular Education Section How to Make it Work I

EVENT PRODUCTION

The Importance of Crafting the Theme

of an Event

In this tool, we share what we have learned about the importance of crafting a theme when planning an event or campaign and what is implied in the process. This advice is based on what we have learned from organizing five Tamejavi Festivals and other cultural and creative expression events.

The event’s theme provides many opportunities for establishing a process for reaching a shared vision and setting common outcomes the group’s organizers would like to achieve. The theme of your event or campaign should be the key message you communicate to let audiences know the intention of your work. It also provides the framework for your focus when designing campaign strategies and event activities. Finally, involving your group in selecting a theme is a great opportunity to unlock the creativities of each member of the group and help them work towards having ownership of the event/campaign.

At the Pan-Valley Institute, we are intentionally thorough when selecting a theme; we dedicate plenty of time, do not rush the process and make sure we consult not only the group that is involved in the project, but people outside the group as well. For example, “A Road to the Future” was the theme of a memory book project that a group of Mexican Indigenous and Hmong women collaborated on and used as a venue to tell their stories in 2003. The women who created this book were between the ages of just 18 and 22. Some were already exercising leadership skills, while others were in the process of learning how to be more involved in social justice issues, but wherever they were on their journey as young women, they were paving a road to their future. Some of those women have become strong leaders either as social justice activists, elected officials or business entrepreneurs.

STEPS TO CONSIDER WHEN CRAFTING A THEME:

1. Pressing Issue of the Moment

Our first step when planning an event, campaign or media project is to pose these questions: What is the issue you want to address through this event, campaign, project? What issue is impacting our communities at the moment; i.e. xenophobia, Islamophobia? Or is there an issue or story we want to reframe; i.e. do we want people to learn that women migrate not only as companions, but as heads of households?

2. Setting Goals

Once we identify the most pressing issue, we set the goals: Why are you doing this? What do you want to change, accomplish?

3. Who is Your Audience?

Who do you want to influence? Who are the people or groups of people that you want to reach?

Once you have discussed these three points, involve your group in crafting the theme. Start by selecting key words that you would like to see in the theme, then start building phrases with those key words. This should lead to selection of a theme that speaks not only to your group, but also to the people you want to influence. This process should be creative, participative and fun!

The initial theme of what is now known as the Tamejavi Festival was “Building Community Through Cultural Exchange,” and after a very creative process, it became Tamejavi. This word represented our main message of opening a space similar to the TAj laj Tshav Puam, MErcado, NunJAVI. It’s derived from Hmong, Spanish and Mixteco words, and represents the space we wanted to create: a marketplace where people gathered to exchange goods, produce, discuss town happenings, and expose their cultural and artistic creativity. TAMEJAVI also connotes the diversity of the Central Valley.

Other Tamejavi Festival themes: Sharing a Journey Celebrating Cultures and Connecting Voice; A Gathering of Indigenous Cultures; Hands that Forge History; and Our Voices, Our Stories: A Path to Inclusion

Principles

• Knowledge built informs and leads to addressing the pressing issues a community faces

• Action is presented to social change with political context

• Multilingual and broad-based communication strategies are important to engaging diverse communities

Tips

• Don’t rush the process; however, you must know your theme before you plan strategies or activities

• A theme can be a strong statement, but shouldn’t be a deterrent

• A theme should be short, ideally three or four words

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Glossary

• Communication and Documentation tools

• Tamejavi Festival Section

EVENT PRODUCTION

Shaping a Festival Program: Dream Big

This tool provides general steps for crafting the program that makes up your event.

The Tamejvi Festival program has included the following components: the blessing ceremony, outdoor marketplace, platicas, film series, and artistic presentations. The following steps provide guidelines for you to consider.

Steps for Shaping Your Program

1. Once your planning committee is in place, committee members must understand that they will play a key role in shaping the festival program in providing ideas, identifying artists and cultural holders, and contributing to the creative process.

2. One of the planning committee’s tasks will be to set the festival’s goals, intentions and outcomes: What do we want to accomplish? What do we want to communicate? What kind of impact do we want to have? The goals and intentions set by the group will help influence the event’s theme. This should be a creative process that, depending on the group, can take two or three meetings and should not be rushed. The theme will influence the message the festival conveys and set the framework for shaping the program.

3. Another important role of the program committee in shaping the program is that once there is a general sense of theme, they will have to go to their communities and identify cultural artists and assets they want to include in program.

4. Once committee members have identified these assets, they share them with their group and start listing potential presenters.

5. When identifying artists in a community, it’s important to share the program’s goals and objectives and to try to convince the artists not only to come as performers, but to share ownership of the process.

6. The process of shaping the program also includes a “Dream Big” session that consists of crafting a creative vision for the event.

7. Allowing this collective process to unfold in shaping the program results in planning committee members taking ownership of process.

8. Since the second Tamejavi Festival in 2004, we implemented pre-festival events that consisted of visiting events happening in the communities the committee members represented, or attending events organized by the planning committee with the intention of building an audience for the festival.

Principles

• Tamejavi incorporates learning from experienced artists, presenters and cultural workers, and believes that participating groups have the capacity to make decisions about the direction and presentation of their work

• There are no set formulas; by encouraging diverse participants to design gatherings and festivals, something new is created each time and learning occurs along

the way

Tips

• Committees should decide when and where to meet

• Try not to saturate the program

• This is a process; it takes time

• Be flexible as shaping a festival program comes with many changes

• Stay focused on the event’s theme

• Be open to people’s creativity

• The program may not be finalized until a few weeks before the event

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Glossary

• Popular Education Section How to Make it Work I

• Tamejavi Coordinating Group Tool

• The Importance of Crafting the Theme of an Event Tool

EVENT PRODUCTION

Example of a Tamejavi Festival Program

EXAMPLE

TAMEJAVI 2007 FESTIVALPROGRAM: HANDS THAT FORGE HISTORY

The theme of Tamejavi IV, “Hands That Forge History,” invites political leaders, the media, community organizations, and the general public to re-examine the basic principles upon which this nation was founded, “with liberty and justice for all,” by resisting the use of labels such as “terrorists” and “illegals” that divide our community and, instead, recognizing immigrants’ traditions, struggles and contributions to Valley life.

BLESSING 8:30–9:15 a.m.

Blessing: by Ron Alec (Mono Tribe)

Music and Dance by Lance Canales

We ask that all who attend be respectful as this is a sacred ceremony, not a performance.

PELOTA MIXTECA 10:15–11:00 a.m.

This is a game with roots in pre-Hispanic cultures played by Mixtecos at the ceremonial centers.

OPENING CEREMONY 12:00–1:00 p.m.

Outdoor Market Stage

Tou Ger Xiong, a Hmong artist and activist, and Rosa Lopez, a Mixteco cultural organizer and storyteller, will facilitate the opening ceremony. By connecting immigrants’ history to the present and looking forward to the future, the opening ceremony conveys that Tamejavi is about our history and struggle to end racism, discrimination and prejudice, and advance justice, equality, human rights, dignity and respect for all.

HISTORY LINE PERFORMANCES

ACT 1: Exclusions and Labor Demands

12:50 – 1:10 p.m.

CONTEXT

The 1924 Asian Exclusion Act prohibited all Chinese, Japanese, Koreans and Indians from immigrating to the United States. Also, by law, Asians could not become citizens, marry Caucasians, or own land. However, farms and canneries still needed inexpensive labor. Thousands of young, single Filipino males began migrating to the West Coast during the 1920s to fill this need. Immigration laws did not exclude Filipinos because they were U.S. nationals since the Philippines was a U.S. territory.

PERFORMANCES

1. Mga Anak Ng Bayan

A student-based Filipino dance troupe formed in 2006, inspired by the Sanpaguipa dance troupe from University of the Pacific. They will present two dances: Pandango Sa Ilaw, which portrays dancers carefully balancing candle lanterns, and Guaway Guaway, a dance that originated in the rice harvest in the Philippine countryside.

ACT 2: Arax

1:15 – 1:35 p.m.

CONTEXT

At the end of the 19th century the first Armenian communities began settling in the Central Valley, playing a critical role in the raisin industry, the largest in the world. Around this time, however, the darkest moments of Armenian history began—the Armenian Genocide of 1915 is known as the first modern, systematic genocide, with the massacre of more than one million Armenians. Today many Armenians call the Valley home, making their group one of the largest populations of Armenians outside Armenia.

PERFORMANCES

2. Arax Dance Group

Arax will present a set of traditional men and women’s Armenian folk dances practiced in the villages of Armenia and passed down through generations of immigrant families.

ACT 3: The Dust Bowl

1:35 – 2:30 p.m.

CONTEXT

The 1930s marked a particularly unstable time for the U.S., which was then experiencing the aftermath of the stock market crash and, consequently, the Great Depression. At the same time, American prairie lands were forced into use beyond their natural limits to capture the profits of World War I, causing a series of catastrophic agricultural events called the Dust Bowl. As a result, about 300,000 people from Oklahoma and Texas, including a group of African-Americans, migrated to the Valley and are now settled primarily in Bakersfield.

PERFORMANCES

1. Jan Goggans

An assistant professor in Literatures and Culture at the University of California, Merced, Jan Goggans has taught courses on the Great Depression and California literature. Goggans is currently completing a book titled “California on the Breadlines.” Jan will present visual, fictional and poetic responses to the great wave of migration to the state of California that occurred during the Great Depression.

Principles

• Tamejavi incorporates learning from experienced artists, presenters and cultural workers, and believes that participating groups have the capacity to make decisions about the direction and presentation of their work

• There are no set formulas; by encouraging diverse participants to design gatherings and festivals, something new is created each time and learning occurs along

the way

Tips

• Committees should decide when and where to meet

• Try not to saturate the program

• This is a process; it takes time

• Be flexible as shaping a festival program comes with many changes

• Stay focused on the event’s theme

• Be open to people’s creativity

• The program may not be finalized until a few weeks before the event

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Glossary

• Popular Education Section How to Make it Work I

• Tamejavi Coordinating Group Tool

• The Importance of Crafting the Theme of an Event Tool

EVENT PRODUCTION

Budgeting for Your Event

This tool provides ideas for developing a festival budget. Having a budget from the beginning is a crucial planning component because it will give you a clear sense of what you can or cannot do for your event. It’s important to create an effective budget that allows for appropriate decisions and clarifies when modifications need to be made.

Steps for Budget Creation

1. List all areas that will need resources.

2. Create a document with two columns: one titled “Projected Budget” and another titled “Actual Budget.” In the projected column, input the estimated budget for each area, and then after the event, input what you actually spent. This allows you to compare your projected budget with the actual expenses.

3. Do your research if needed; for example, call around to get quotes from different vendors, venues and equipment rental companies.

4. Decide whether purchasing items or renting them is most beneficial to your event.

5. Consider whether financial assistance can be obtained from other sources such as donations, in kinds, ticketing or sponsorships.

EXAMPLE:

If you have a budget of $40,000, you must allocate the available funds amongst the following areas, or other areas you may identify.

• Venue rental

• Equipment rental

• Outdoor market

• Technical production team manager

• Outdoor market curator

• Consultants

• Performing group stipends

• Travel and lodging for performers

• Travel for staff

• Food and beverage for pre- and post-festival events

• Translation services

• Printing of publicity materials

• Supplies, decorations and exhibit materials

• Volunteer coordinator

• Additional resource people

• Planning committee meetings

• Communications/promotion/outreach/building audiences

• Festival film series

Principles

• Tamejavi activities grow organically from and are democratically organized by members of the Pan-Valley Institute and program committee

Tips

• The budget is a living document, so it may need to be updated every so often

• Assign someone to constantly check the budget and keep it on track

• Be careful with last minute expenditures