Who is a Cultural Organizer?

This tool list the abilities of a cultural organizer and provide ideas for identifying, recruiting and engaging groups of people in cultural organizing.

What Makes a Good Cultural Organizer?

A cultural organizer is someone who:

• Is committed to community work and collaborative processes

• Listens to the concerns and dreams of the community

• Understands the daily issues in the community and also

has a larger vision

• Makes links and connections between people, places and organizations

• Makes sure that the issues of the community are addressed

• Brings people together

• Knows how to build relationships in the community

• Understands the cultural patterns and understandings

of their community

• Comes from a diverse cultural background, believes in

collective learning and social change, and is committed

to making a more just and democratic society

• Has understanding of the economic, political and social

impacts that have shaped the immigrant and refugee communities

• Shares cultural organizing values and principles

Profile of a Cultural Organizer

Brenda Ordaz was born in Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico. The daughter of Zapoteco farmworkers, she was constantly on the move as a child until settling in Madera, Calif. at the age of 11. Besides attending college and working as an organizer for the Coalition for Human Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles, Brenda is also a committed cultural promoter. She spearheaded a youth dance ensemble to perform at the Fiesta del Pueblo, a yearly event in celebration of San Juan, the saint of her hometown. The Fiesta del Pueblo is not only a religious ceremony, but also the time of the year in which Zapotecos living in Madera have a space to play music, dance and display their art, culture and food. Brenda believes that this event gives a sense of belonging for youth and children of immigrants. She also wrote and performed in “The Fandango Zapoteco,” a play representing a traditional wedding.

By attending and organizing cultural events, Brenda has discovered the great needs and the organizing potential of the Zapoteco community.

During her time in the Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program (TCOFP), Brenda learned about cultural organizing practices by forming a learning group. She identified six people from her community and invited them to be part of her group. After the initial meeting in which she shared with them about her role as a TCOFP fellow and what their role in her learning group would be, she involved them in her community assessment and cultural inventory. The group later used what they learned to present a play telling the story of migration in her community. As a cultural organizer, Brenda was in charge of all the group’s meetings and activities while supporting their involvement and being receptive to their needs. At the end of her fellowship, she facilitated follow-up meetings in which group members shared what they learned about creating a space for their community to tell a story in their own voices.

“I want to plant a seed that will help my fellow immigrants develop a feeling of belonging, creating a strong sense of identity and personal strength to help them act on the issues that affect their lives.”

Brenda Ordaz

Principles

• Creating a space for the expression and reproduction of indigenous artistic and cultural knowledge is a decolonization step

• Cultural organizing is a collective process that works with groups, not just individuals

• Popular participation in cultural production is integral to community life and civic engagement around the world

Tips

• Be connected to the community

• Build community trust

• Have time, commitment and passion to engage in activities and follow through on the work agreed upon

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• Learning Groups tools

• TCOFP tools

Cultural Organizer Vignettes

This tool shares profiles of cultural organizers that participated in the Tamejavi Cultural Organizing Fellowship Program (TCOFP).

Pov M. Xyooj was born in Long Beach, Calif. His parents are Hmong refugees who were sponsored to come to the United States from a Thai refugee camp through his mother’s father. He is the first in his family to be born in the U.S., and became the first to graduate from a four-year university when he earned a B.S. in physics and a minor in Asian American studies from UCLA. While in college, he was involved in several Asian student organizations, including Vietnamese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino and Hmong associations. Pov moved back to Fresno, where his parents live, after college and immediately started building connections with local Asian student organizations and community leaders. Through this work, Pov is not only reconnecting with his cultural roots and immersing himself in the Hmong community, he is taking action to redefine his identity by composing and performing bilingual hip-hop music and reclaiming his original Hmong family name.

Silvia Rojas is a native of Santiago Tiño Mixtepec, Oaxaca, Mexico who came to the United States in 1992 at the age of 17. Silvia speaks her native Mixteco, Spanish, and understands some English. Like many other women from low-income immigrant families, Silvia assumed major social responsibilities from a very young age, including running her hometown medical clinic at the age of 13. Since moving to the U.S., Silvia has worked in agriculture, harvesting onions, garlic and strawberries. Now married and the mother of two boys and three girls, Sylvia no longer works in the fields and dedicates much of her time to community work. Besides her commitment to motherhood and community organizing, Silvia loves dancing and has participated in the traditional dance group Se’e Savi in Madera, Calif. As her commitment to the dance group’s community work grew, she became a member of Se’e Savi’s organizing committee. In 2006, Silvia was invited to participate in a project called Naaxini (leader) where she learned to be a health leader to help the indigenous immigrant community.

“Ultimately, cultural organizing utilizes culture and art as a venue and resource for strengthening immigrant leadership and building a sense of place and belonging that inspires and promotes active participation in public life.”

Juan Santiago

Principles

• We give people the tools they need to make changes in their communities

Tips

• To be a cultural organizer, you must be willing to invest time and have a special interest in the cultural vitality of the community

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• TCOFP tools

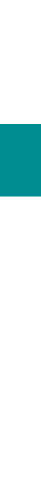

Graphic Facilitating

Graphic facilitating has been a tool since the early years of the Pan-Valley Institute’s inception.

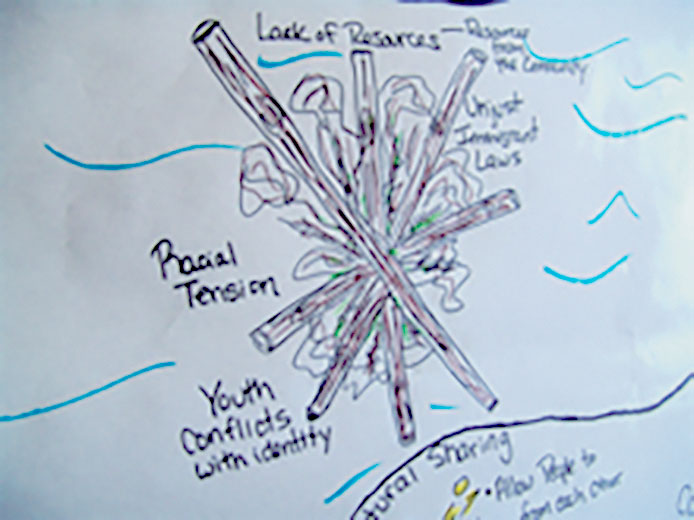

In this tool, we share an example of a poster developed to describe the steps of a cultural organizing process and the journey cultural organizers take to reach a vision. In the clouds, we describe the intention of cultural activities, the boat indicates the cultural organizers embarking on their journey and the different steps they take to reach their vision, along with the obstacles they face. It includes the people they meet and bring together in the process and the different events they organize before the culmination of the journey.

Principles

• There are no set formulas; by encouraging diverse participants to design cultural and art series, festival and other cultural sharing events, something new is created each time and learning is created each time

Tips

• Be creative, as creativity is the key to this process

• Develop your own approaches

References

• The Theory Behind Our Work booklet

• How to Facilitate the Popular Education Process Tool

• The Practitioner’s Role in Popular Education Tool